The Global Political Landscape of Indonesia’s Semiconductor Ambitions: A Humble Reflection

Dr. Galih R. Suwito is Lecturer in Dept. Electronic and Electrical Engineering at University College London (UCL), United Kingdom. Achmad S. Hidayat is a doctoral student in Dept. Chemical Systems Engineering at Nagoya University, Japan. They are Director and Deputy Head of INEST – Indonesian Strategic Network for Semiconductor Technology, respectively.

Indonesia's industrial policy of “hilirisasi” (downstreaming) has been a major awakening for the country to strengthen its domestic manufacturing [1]. Despite strong domestic demand, the country is more than a decade behind its Southeast Asian neighbors in terms of semiconductor industry [2]. This places electronics and semiconductors as the third-largest import after oil and gas in Indonesia, highlighting a deep dependency in critical sectors, such as automotive, telecommunications, and defense [3]. In the global semiconductor supply chain, Indonesia’s role remains minimal with a few activities in chip design (fabless) and assembly (termed backend manufacturing) rather than in the more lucrative “real chipmaking” segment of the supply chain (fab or front-end manufacturing). Even in the labor-intensive, low value-added backend manufacturing, the country still lags behind regional peers like Malaysia, Philippines, and Vietnam [2].

Hilirisasi.

At the same time, global dynamics around critical minerals, clean energy, and advanced manufacturing have shifted rapidly. The 2024 G20 summit in Rio de Janeiro placed secure and sustainable supply chains, including for semiconductors at the core of the energy transition agenda [4]. This year’s 2025 G20 summit in Johannesburg went further, adopting a G20 Critical Minerals Framework to promote resilient, transparent, and value-adding mineral value chains explicitly including materials and technologies underpinning semiconductor [5]. For Indonesia, which sits on vast reserves of nickel, copper, bauxite, and other critical minerals, these developments are not abstract diplomacy they define the playing field on which Indonesia’s semiconductor ambitions will either flourish or fade.

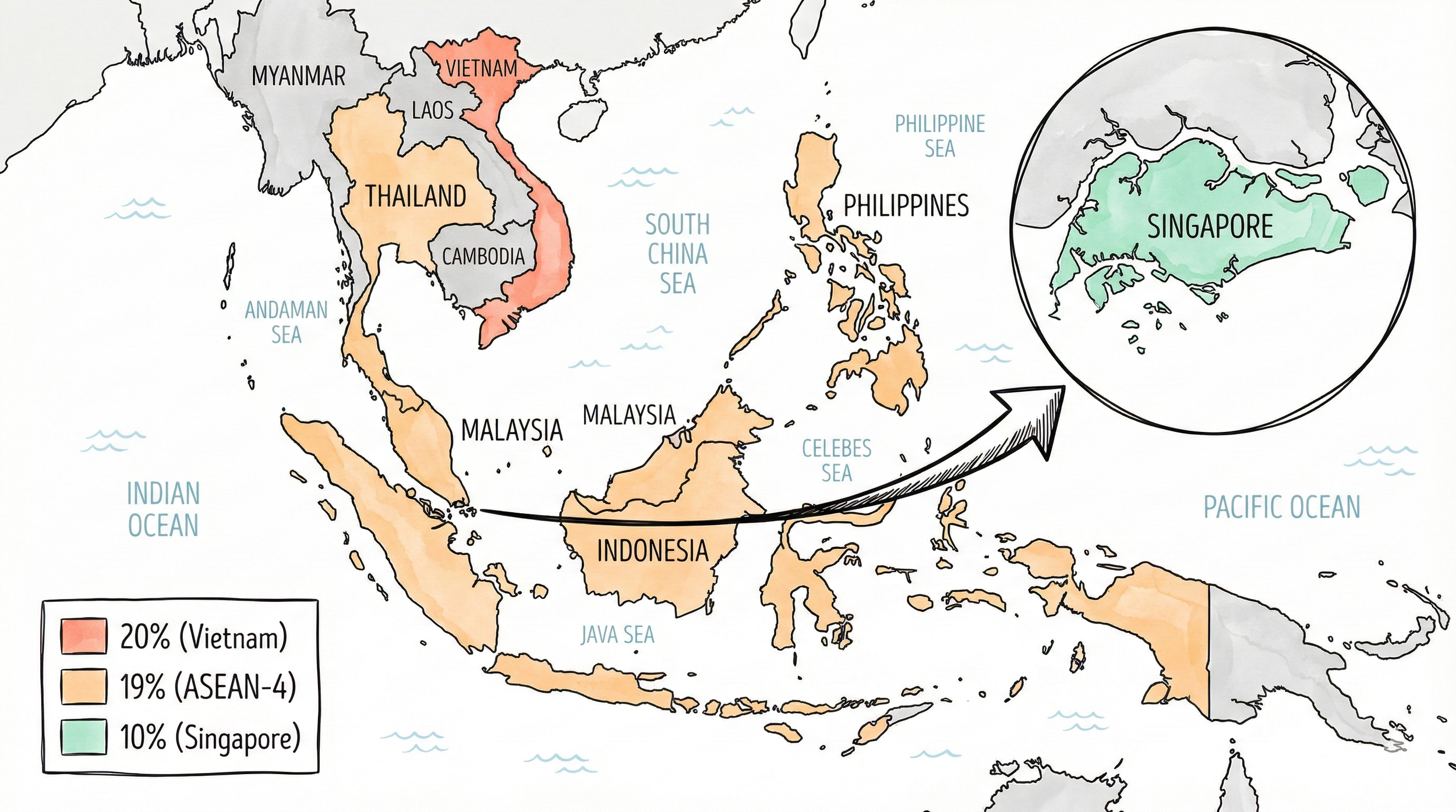

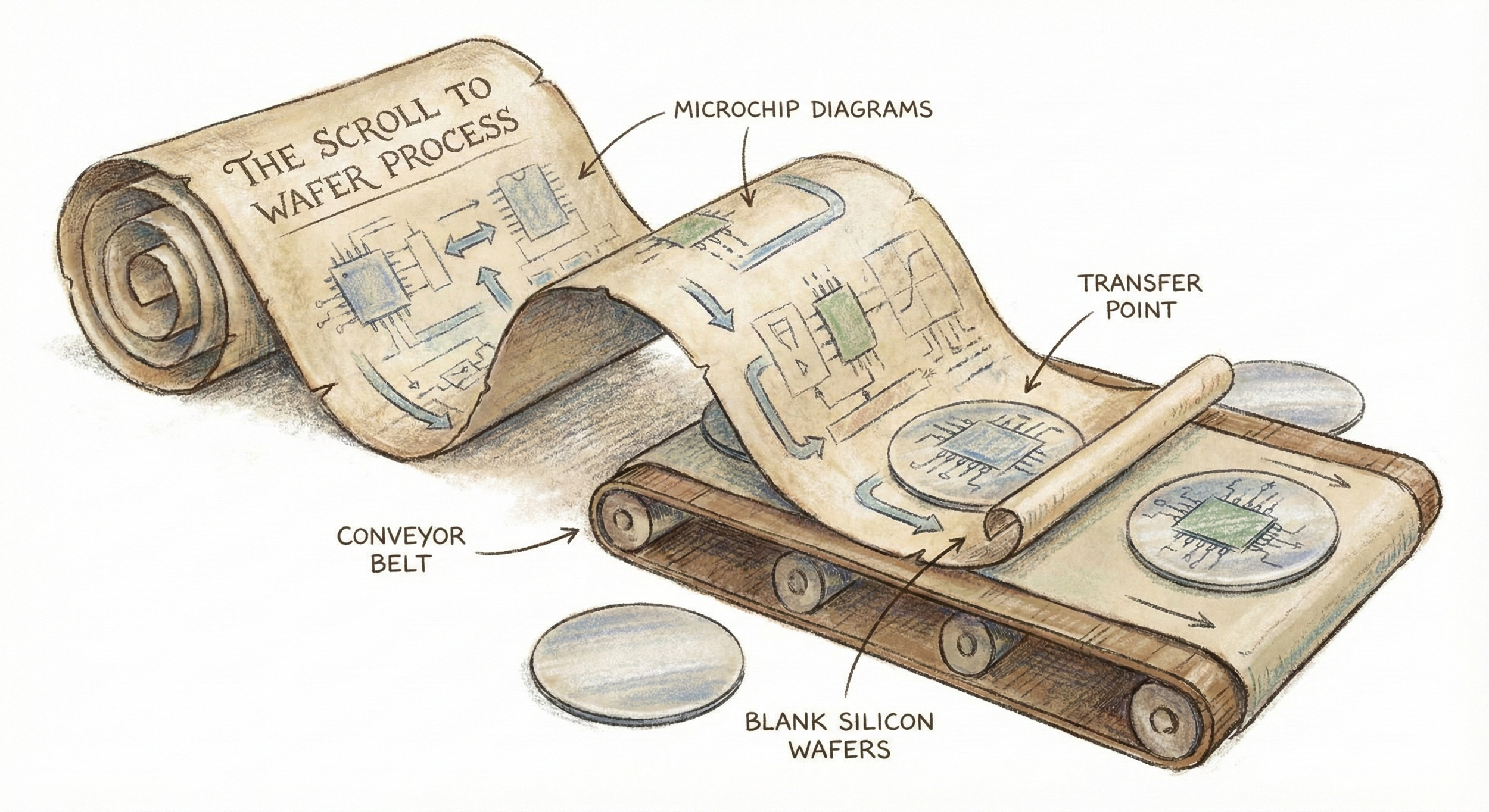

The global political and economic landscape has been tricky for Indonesians especially after the recent US-Indonesia reciprocal tariff agreement, cutting rates for Indonesian exports to the US from 32% to 19%, while removing tariffs on US exports to Indonesia [6]. This has added a new dimension to Indonesian semiconductor ambitions. Establishing a front-end semiconductor manufacturing facility is a capital-intensive business requiring investments of at least USD 10 billion per fab. This high cost comes from acquiring advanced equipment for hundreds (to over a thousand) of process steps, each requiring highly specialized tools. With US imports now facing a 0% tariff, Indonesia gains easier access to critical American-made tools. Except for photolithography systems, dominated by the Netherlands’ ASML, the US is the world’s leading supplier of semiconductor manufacturing equipment, with industry leaders such as Applied Materials, Lam Research, and KLA. In addition, the reduced export tariff of less than 20% on most ASEAN countries brings additional stability in the region for FDI flows.

Different tariffs within ASEAN countries.

However, this regional tariff landscape complicates Indonesia’s competitiveness. Singapore, with its preferential 10% tariff [7], strengthens its position as a hub for high-value exports, particularly in pharmaceuticals, biotechnology, and electronics. Its advanced logistics infrastructure, coupled with strong intellectual property protections, makes Singapore the natural gateway for US companies seeking an ASEAN production base. Vietnam, despite a marginally higher 20% tariff, continues to attract substantial FDI due to its established manufacturing ecosystem, robust electronics supply chains, and aggressive government incentives [8,9]. Major technology giants such as Samsung and Intel have already consolidated Vietnam’s role as a critical node in global semiconductor production, allowing the country to offset tariff disadvantages with sheer production capacity and integration into global value chains. Malaysia, the Philippines, and Thailand, countries that, like Indonesia, face a 19% tariff, nonetheless enjoy stronger industrial ecosystems [10]. Malaysia and the Philippines have been central players in semiconductor backend manufacturing for decades. Thailand, while more concentrated in automotive electronics, also benefits from deep integration with Japanese and Western supply chains. Even at equal tariff levels, Indonesia lags behind its peers in terms of industrial readiness, skilled labor availability, and overall export competitiveness.

The situation is further complicated by the 0% tariff now granted to US exports entering Indonesia. While this provision was framed as a step toward balanced trade, in practice, it risks overwhelming domestic industries. Consumer electronics, telecommunications equipment, and IT hardware from the US, often technologically superior and backed by economies of scale, will now enter Indonesia “duty-free”. Local small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), already constrained by high production costs, limited access to capital, and gaps in research and development, will struggle to compete. Over time, this could hollow out Indonesia’s electronics base, making it harder for domestic firms to scale up or achieve international competitiveness.

The US–Indonesia tariff deal sits alongside another critical negotiating track, ongoing discussions on critical minerals and joint investment with the United States [11]. Indonesia has floated proposals for joint projects via its sovereign wealth fund, hoping to lock in both capital and market access while easing tariff pressures. These negotiations now unfold in a world where G20 partners have collectively endorsed fairer, more resilient mineral and technology supply chains under the Critical Minerals Framework.

This creates a complex, but potentially advantageous, diplomatic geometry for Indonesia. By aligning its domestic hilirisasi agenda with the G20 Critical Minerals Framework, Indonesia can argue that value-addition, technology transfer, and environmental safeguards are not “protectionist deviations,” but part of an emerging global norm. Cooperation with African, Latin American, and other Asian producers of critical minerals can help Indonesia avoid a race to the bottom in tax breaks and deregulation, and instead push for shared standards on downstream investment and technology partnerships.

Indonesia’s new finance minister, Purbaya Yudhi Sadewa, has become a central figure in shaping how the country will use its fiscal tools in the next phase of industrialization. Since taking office in September 2025, he has presented himself as a pro-growth policymaker who is willing to use the state budget more aggressively [12,13]. Crucially for semiconductors, Purbaya has said the government will prioritize foreign investors willing to transfer technology or generate strong spillovers for the domestic economy. Sectors where Indonesia still lacks critical know-how will be opened more widely to such investors, on the condition that they help build local capabilities rather than just extract rents [14].

The 2025 G20 summit In South Africa signaled that the world is willing to rethink how critical minerals and advanced technologies like semiconductors are governed. But frameworks and declarations do not build fabs, train engineers, or sustain SMEs. That work must be done in Indonesia, through consistent policies, capable institutions, and strategic partnerships that align with both hilirisasi and global norms on sustainability and equity. The tariff gamble, in other words, will only pay off if Indonesia treats the G20 not just as an opportunity, but as a mandate to build a coherent, long-term semiconductor strategy at home.

Reference

[1] Indoneisa’s Critical Minerals Moment: Turning Resource Wealth into Rules-based prosperity

[2] Indonesia's Semiconductor Industry: Towards Realising the Potential for Growth, https://ocivvlhqiwtxvnycqnia.supabase.co/storage/v1/object/public/new-kerko/5964260/4T9D9I4V/QP7SDYDG/file.pdf

[3] Observatory of Economic Complexity (OEC)

https://oec.world/en/profile/country/idn

[4] G20 Rio de Janeiro Leaders’ Declaration

https://www.gov.br/g20/en/documents/g20-rio-de-janeiro-leaders-declaration

[5] G20 South Africa Summit Leaders’ Declaration

https://dirco.gov.za/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/2025-G20-Summit-Declaration.pdf

[6] Indonesia to cut tariffs, no tariff barriers in US trade deal

[7] Singapore Tariffs 2025 | US Tariffs on Singapore

https://www.theglobalstatistics.com/singapore-tariffs/

[8] Vietnam to launch investment incentives for semiconductor industry

[9] Vietnam’s Semiconductor Industry: Progress and Outlook Beyond 2025

https://www.vietnam-briefing.com/news/vietnam-semiconductor-industry.html

[10] U.S. Tariffs in Asia 2025 – A Regional Investment Map

https://www.aseanbriefing.com/news/u-s-tariffs-in-asia-2025-a-regional-investment-map/

[11] Indonesia still negotiating details, exemption on US tariff deal, official says

[12] Plain speaking economist, Purbaya, takes helm as Indonesia's finance minister

[13] Indonesia says banks must use government liquidity boost lending

[14] Indonesia Prioritises Foreign Investors Committed to Technology Transfer